A production boom has turned New York into a TV town. But how long will it last?

By Addie Morfoot

Crain’s New York Business

Sarah Jessica Parker began work in February 2015 on the pilot episode of Divorce, her first series since starring in the smash hit Sex and the City, which ran for six seasons on HBO, led to two motion pictures and inspired a bus tour throughout the city that still sells out to die-hard fans 12 years after the show ended. Though Divorce, which premiered Oct. 9, was among the most highly anticipated shows of 2016, Parker’s star power mattered little when it came to finding a soundstage in New York City to shoot the series.

Silvercup Studios in Long Island City, where many interior scenes of Sex and the City were shot, didn’t have a vacancy at any of its two dozen soundstages. Instead of choosing one of the 70 soundstages at the three other major New York City studios, HBO picked a lesser-known facility with fewer amenities in Greenpoint: Cine Magic East River Studios.

“It’s really hard to find good-quality stage space in the city,” said Clyde Phillips, an executive producer who has served as the showrunner for AMC’s Feed the Beast.

New York City is in the midst of an unprecedented TV production boom, one that contributed $8.7 billion to the local economy in 2015, an increase of more than $1.5 billion, or 21%, since 2011, according to the city. Employment in the motion picture and video industries grew by nearly 44% in New York City between 2009 and 2013, while the United States as a whole saw only a 6% increase, according to the state Department of Labor, with employment directly related to film and television reaching 130,000 people in 2012.

That growth has put soundstages in short supply, creating maddening problems for television production companies while spurring property owners to keep up with demand by investing tens of millions of dollars in new and renovated stages. Established studios are furiously expanding throughout the five boroughs, while newcomers are converting industrial spaces in the city and in the northern suburbs into stages. Even entrepreneurs farther upstate are angling for a piece of the action. They are pressing Gov. Andrew Cuomo to sign legislation that would give economic incentives to productions that film north of Rockland and Westchester counties and in Suffolk County.

“Everybody who wants to work in New York is working,” said production supervisor Chris Collins. “We are even bringing in people from out of town to work on our shows.”

Looming over this building frenzy, however, is uncertainty over the state’s $420 million film tax-credit program, which is universally seen as the catalyst of the TV boom but is set to expire in 2019. If the tax credit is not renewed, many insiders say the TV industry in New York will dry up and thousands of jobs will be lost.

“Absent the tax-credit program, we are going back to empty warehouses,” Silvercup Studios CEO Alan Suna said. “Ninety percent of the facilities would go away, no doubt about it.”

Origins of a tax break

At the time the state passed its film and TV tax credit in 2004, productions came to New York City primarily for location or exterior shots and then headed to Canada to film everything else. Producers told The New York Times that year that this way of working saved them from $5 million to more than $50 million per production.

To keep productions here, the state offered a 10% credit on qualified “below the line” expenditures. Movie-star salaries as well as writer, director and producer credits are considered above the line, whereas below-the-line costs include everything else: the crew, the equipment, the insurance and more. But the credit led to only $25 million in savings—not enough to change the calculus for most productions.

In 2008, the state expanded the credit to cover 30% of qualified expenditures. The change worked. According to a study conducted by Camoin Associates for the Empire State Development Corp., the increase in production was “faster than the overall industry growth in the United States.” In 2003, 18 films and seven television shows were shot in New York state. By 2013 that number grew to 181 films and 29 TV series.

The tax credit, however, came with a key caveat: to get it, productions had to use a soundstage in New York. That requirement created a steady revenue stream for studios. According to several producers, renting a stage along with office space and dressing rooms and building workshops in New York City can range from $100,000 to $300,000 per month. That does not include studio equipment rental fees, which are required by the four major studios: Broadway Stages in Brooklyn and Long Island City; Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens; Silvercup Studios in Long Island City and the Bronx; and Steiner Studios in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

The Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment issued 12,205 filming permits across all five boroughs in 2015. While not all of the productions that applied for permits take advantage of the state tax credit, the great majority do, putting space in short supply. High-profile, high-budget shows including Showtime’s Homeland and Cinemax’s The Knick found production homes at one of the many converted warehouses that are popping up around the city. Other shows, including Amazon’s Red Oaks, couldn’t even find space within the five boroughs, ultimately filming in Westchester and Rockland counties instead.

The demand for space is made worse by scheduling problems.

Movies out now

The production boom focused on New York has one blurry spot: big-budget movies. Broadcast and cable television and digitally streamed shows are pushing feature films whose production budgets average $67 million out of the five boroughs.

According to a FilmL.A. study released in June, New York City hosted just seven of the 109 major feature films in 2015, down from 13 the prior year. California hosted 19 last year, the United Kingdom 15, Georgia and Louisiana 12 each, and Canada 11.

TV series, which can rent a soundstage for 10 weeks to a year, are studios’ first choice for a tenant, according to producers. And with TV production demanding space at unprecedented rates, movies cannot compete for quality spots. “There is more safety and longevity [in television], and if you have the choice between the two you are certainly going to go for the safer, more secure and longer production,” said Scott Levy, founder and president at Eastern Effects, a studio space in Gowanus, Brooklyn. “As a businessperson, I have a lot of bills to pay.”

Therefore feature film productions are in a difficult position, with few good choices. Location manager Joe Guest, whose credits include Money Monster and The Girl on the Train, recently worked on a Netflix feature film, Okja, starring Jake Gyllenhaal and Tilda Swinton. Guest said that the film did not take advantage of the state’s tax credit because most of it was shot in South Korea. So the production filmed in a boat repair warehouse, Agger Fish, at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, rather than at a city soundstage that could have qualified it for the credit.

“If we had needed a qualified production facility for that project we would have had to go to Bethpage [Long Island], because Grumman and Gold Coast might have been the only stages available.”

Grumman Stages and Gold Coast Studios are high-quality soundstage spaces that have been used for films including The Amazing Spider-Man,Salt and HBO’s upcoming Bernie Madoff movie,The Wizard of Lies, but they are about 30 miles from Manhattan.

“They are huge and have lots of parking, but the distance is a real drawback for most productions,” Guest said. “I’ve heard producers say, ‘If we have to go to Bethpage then maybe we should go to Atlanta or Boston instead.’ ”

Doug Steiner, CEO of Steiner Studios, said films will shop far and wide for the most generous tax credit, “whereas New York has a built-in infrastructure, crew base and talent base for TV here,” he said. “And that’s really why film sometimes gets crowded out.”

Unlike the classic network TV show model where a production books a stage from August until May to shoot 22 episodes, Netflix, Amazon and HBO, Showtime and other cable networks often shoot a 10- or 12-episode season at various times throughout the year and can easily overlap, leading to a lack of space during peak production times.

“I like to keep my stages full, but I have availability every few months,” said Doug Steiner, chairman of Steiner Studios. “We are essentially a boutique hotel. People come and people go.”

Vacancies do come up: Suna said that Silvercup has stage space available due in part to the conclusion of HBO’s Girls. But only short-term productions can make use of the space.

“The Girls stage is not booked with another TV show until mid-December,” Suna said. “Also the stage where Netflix was filming Z is empty. I booked a two-week commercial, and I’ll continue to fill it in with spot work.”

Spotty scheduling and the periodic space crunches that result are likely to grow as original cable and streaming programming proliferates. In the past year, the city played host to 52 episodic television shows; 28 broadcast, cable and digital pilot productions; seven major, high-budget motion features; approximately 330 smaller-budget films as well as myriad independent films and commercials. When Collins worked on the CBS show Limitless, Broadway Stages found the production a soundstage, but it was an unusual choice. “It was an old bowling alley they converted into a stage in Ridgewood, Queens,” he said, adding: “Everything is pretty booked up. It’s gotten more and more difficult in the past few years.”

Filling the gap

With the more established studios booked solid during key times of the year, a cottage industry has formed of entrepreneurs transforming warehouse facilities in the city and northern suburbs into stages. Greenpoint’s Cine Magic East River Studios hosted Showtime’sHomeland. In Westchester, Alexander Street Productions in Yonkers rented space to the box office hit The Girl on the Train and Haven Studios in Mount Vernon housed Hulu’s The Path for two seasons. Eastern Effects, a soundstage in Gowanus, Brooklyn, has been home to FX’s The Americans for the last five years. (In 2021 the city plans to use eminent domain to demolish the studio’s main 40,000-square-foot facility at 270 Nevins St. as part of its effort to clean up the Gowanus Canal, a federal Superfund site.) Eastern Effects founder Scott Levy recently opened a new soundstage in East New York, Brooklyn, where a VH1 show is currently filming.

Nicole and Gabrielle Zeller of consumer products company Zelco Industries are newcomers. The sisters transformed the family-owned warehouse and manufacturing facility in Mount Vernon into Haven Studios in 2013 after the company downsized in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The sisters, who did not have any film or TV experience, moved company operations to the warehouse’s basement and converted the ground floor into a stage they have rented to Saturday Night Live skit productions, the HBO series The Leftovers, in addition to The Path.

“We once had a photographer in here who said it would make a perfect production space,” Nicole said. “So we went online and figured out how to do it and then marketed it on [the state] website.”

Demand for high-end stages

Warehouse conversions do not offer all of the amenities that the larger studios do, according to Collins, who is currently working on the third season of The Affair. The Showtime drama filmed its first season at Broadway Stages, its second season at Steiner and its third and current season at Kaufman Astoria. “Steiner, Kaufman, Silvercup and Broadway Stages have the support systems, the offices, the dressing rooms and are clean and professionally run,” he said. The big four “have everything you need while the warehouses just don’t have the same level of upkeep and professionalism.”

Phillips said that in the rush to meet demand, the quality of the studio space in the city has suffered. Along with Feed the Beast, he also served as showrunner for Showtime’s Nurse Jackie. Both series were filmed at Kaufman Astoria.

“There are buildings that are designated as stages so that the tax break can go forward that are not really stages and do not offer the high-quality facilities that someone like Kaufman Astoria offers,” Phillips said.

That criticism has given the major studios’ expansion plans greater urgency. Silvercup recently opened a $35 million, three-soundstage facility, dubbed Silvercup North, in the South Bronx. In June, Kaufman Astoria Studios announced the construction of two new soundstages on its Astoria campus, bringing the total number of stages at the complex to 12. Broadway Stages operates more than 20 stages in Brooklyn and Queens. In February 2014 it announced plans to invest $20 million to redevelop Staten Island’s old Arthur Kill prison into a movie backlot with five soundstages. (Construction on the 69 acres had been held up due to land transfer issues.)

Six stages are currently being added to Steiner’s 26-acre Brooklyn Navy Yard lot—which will bring the total to 30. Steiner said he won’t stop expanding until his facility houses 40 stages.

“We started in 1999,” Steiner said. “We are 17 years into it, and we will keep going until we are a full 60 acres and have 40 (stages) and we have that critical mass equivalent to the lots in Los Angeles.”

Looming expiration

The industry, though, must navigate growing tensions between the city, which has benefited enormously from the tax credit, and the rest of the state, which is still looking to cash in.

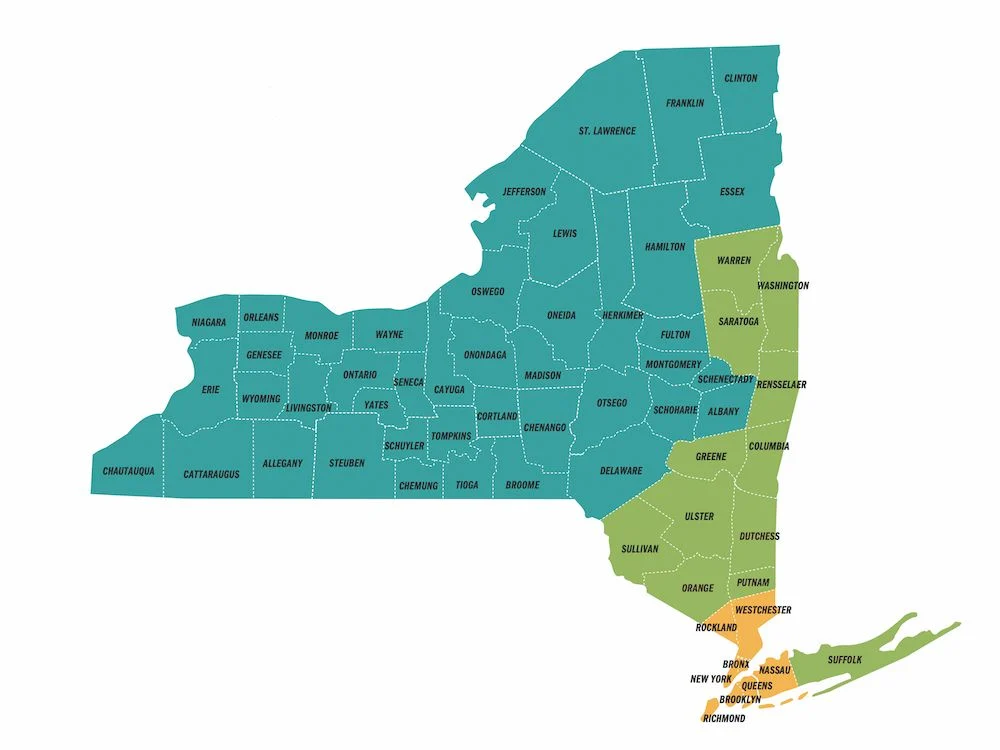

New York’s film tax credit applies to all 62 counties of the state. But to stimulate production in counties outside of New York City, state officials in 2014 increased the 30% fully refundable tax credit to 40% for shows and films with budgets over $500,000 that are made in 40 upstate counties. In 2015, Albany and Schenectady counties were added. Now Democratic Assemblywoman Aileen Gunther from Sullivan county in the Catskills wants to include the Hudson Valley (north of Westchester and Rockland counties) and Suffolk County, which are close enough to the city to draw the kinds of productions that shoot here now.

In the bill, Gunther states that “while this incentive has had a positive impact on the film industry upstate, it has unfortunately had a negative impact on other parts of the state, namely the Hudson Valley and parts of the Capital Region and Long Island. These areas are becoming film flyover counties. These counties cannot afford to be off-limits to this important and lucrative industry.”

Productions in blue counties benefit from a 40% tax credit, while areas in yellow receive a 30% tax credit. Currently, counties marked in green receive 30%, but a proposed change would increase that to 40%.

“I don’t know why they left us out to begin with,” Gunther said. “It’s annoying. We’ve got it all up here.”

If the governor signs Gunther’s bill, it will go into effect immediately. But if the tax credit itself is not extended before it expires in 2019, none of that will matter. Even though Cuomo attended the ribbon cutting for Silvercup North, the extension would still have to go through the Assembly and state Senate, whose members might have their own ideas for how—or if—the credit should be extended. In the meantime, producers are beginning to feel like they are in limbo. TV productions usually sign multiyear deals, and many are unlikely to want to shoot in New York if it means moving to another city partway through the contract.

“It’s a conversation I have with someone at least once a week: “It’s really crazy now, but how long will it last?” Collins said. “It’s in the back of everybody’s mind that this could go away. Everyone has some degree of fear over that.”